By Bryson Torgovitsky

On 28 January, Professor Takayuki Yoshioka of Okayama University came to our class and told us about his school’s normal program and the extended Discovery program. I was surprised to hear about the price of Okayama University’s tuition, a little less than $5,000, and the price of their normal housing, $100. My sister has been going to the College of Charleston in South Carolina, but I frequently overhear my parents and her complaining about the expenses of college. Since she is paying for college out of state, the price of her overall expenses during her 2015-2016 school year was just over $28,000. This is about five times more than Okayama University’s tuition and housing fees combined. Professor Yoshioka even told us that the tuition fee could receive a 50 to 100% waiver!

The reasonable price of Okayama University caught my eye first, but the Discovery program sealed the deal for me. I have a personal desire to study marine biology, and the promise of a school with a program that encourages foreign exchange students is very appealing to me. Besides the Discovery program’s expression of Okayama University’s intention to host exchange students, Professor Yoshioka told us that the Discovery program presented eligible students with a monthly research grant of $350. The potential for an affordable education in a country that I want to learn more about, with an additional grant so that I can fund my marine biology research, are more than reason enough for me to plan to apply to Okayama University next year when I am a high school senior.

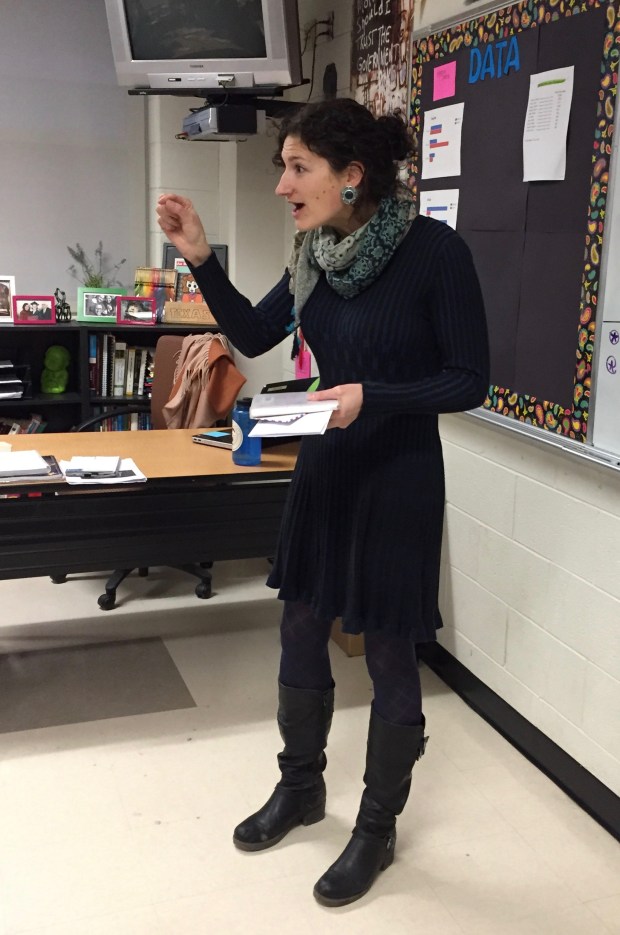

While in the Japanese Plus Program, I have been informed by multiple presentations by various visitors. One of the most interesting visits was Stouder-Sensei’s visit. She was a foreign language teacher from Washington Latin who spoke of how she learned Japanese and the struggles she went through. Most importantly, she provided us with tips on how she overcame obstacles with learning Japanese and the determination she applied to her desire of learning Japanese.

While in the Japanese Plus Program, I have been informed by multiple presentations by various visitors. One of the most interesting visits was Stouder-Sensei’s visit. She was a foreign language teacher from Washington Latin who spoke of how she learned Japanese and the struggles she went through. Most importantly, she provided us with tips on how she overcame obstacles with learning Japanese and the determination she applied to her desire of learning Japanese.